Prada, and the Cult of the Ugly

Prada’s SS21 Dialogues ad campaign.

There is a word in fashion that you’ll hear in every meeting, elevator pitch, or cocktail party: aspirational.

From the show-notes—the written manifestos/press releases distributed on the seats for guests to understand the collection just before it’s presented on the runway—the casting choices, color trends, or even perfume ads, in fashion every construct of beauty is impregnated, designed and produced with the idea of being better—of becoming better.

But in order for enhancement to come into the scene, one has to first acknowledge the flaws in the room.

The Cult of the Ugly

The quest for beauty is no recent conundrum, it dates back to Ancient Greece when it would be the topic of endless afternoons between Plato and Aristotle; later in the 18th century, Kant developed aesthetics, a separate branch of philosophy that theorized beauty and eventually shaped many of today’s standards.

The Romantics wrote about it, the French were obsessed with it—all through Baudelaire and Zola—but it was in 1909 Italy where the founder of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote, “There is no more beauty. No work without and aggressive character can be a masterpiece,” shaking the European perspective of the classic and the beautiful.

All of these ideas ended up on the desk of a young Italian political-science student who after being raised in a strictly patriarchal family finally saw herself out of the nest and yearning for a revolution.

NAÏF AND IDEALIST

The granddaughter of Mario Prada, Miuccia grew up in a family that constantly told her that “women should stay at home.” Later in her life, her youthful idealism and non-conforming ideas would clash with the different social uprisings of the 1970s. Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

A feminist and Communist, Miuccia was no longer little Miu Miu (her childhood nickname) constricted by Catholic and conservative values—although these would eventually shape many of her future endeavors—she was now a woman with convictions and ambitions.

After her degree, she abruptly changed course and trained as a mime at Milan’s avant-garde Piccolo Teatro. This might come as random but nothing in Miuccia’s life happens par hasard, as previously noted by writer Judith Thurman, “Mime like fashion is a silent art, and in both cases, a practitioner has to imagine how the language of a body expresses the emotion.”

THE PRADA BEAUTY

If there’s something Miuccia Prada has achieved is making ugly beautiful, complex, and intellectual. All of her creative decisions, whether on the runway or off, come from a point of refusal.

Oftentimes categorized as an emblem of postmodernism, Miuccia says she “isn’t anxious enough.” But there’s no doubt her skirts are designed not just to stay at home, they are meant for intellectual upheavals and social revolution. “Most of my work is concerned with destroying—or at least deconstructing—conventional ideas of beauty, of the generic appeal of the beautiful, glamorous, bourgeois woman,” she once said in an interview, “Fashion fosters clichés of beauty, but I want to tear them apart.”

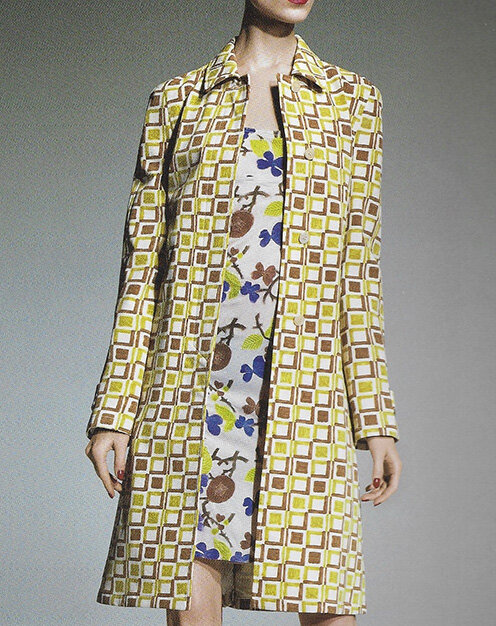

“My spring 1996 collection was an exercise in elevating cheap and obsolete patterns into high fashion. The patterns recalled trashy textiles used for curtains and tablecloths in suburban homes. As well as being an exercise in elevating ordinary, it was also an exercise in trompe l’oeil, as the patterns were not in the weaves.”

“People say that my designs are quirky, but they’re not quirky. I deliberately introduce a steady look into high fashion. So what people sometimes interpret as quirky is my attempt to subvert the concept of luxury by introducing elements that are considered ordinary of commonplace.”

In the Prada lexicon bad taste is taste. In her collections you will find two, three or maybe four things that don’t make any sense, together. Contrasting materials (both organic and highly synthetic), colors—lots of brown, since “it’s a color no one likes”—and textures are just some of the devices Miuccia uses to upend prescribed concepts we’ve all aspired to at some point in our lives. “It isn’t that Prada undervalues beauty’s power, but she wants you to understand its pathos,” as also written by Thurman.

Nevertheless, Miuccia’s loudest clamor is off the runway. A late bloomer in the fashion tracks, she presented her first collection at the age of 40 and at 77 is still considered the world’s most influential designer. Age, same as beauty, holds no constraints.

She’s a designer that’s not interested in a style, she explores ideologies and norms to twist them in oblique manner—subversive and wicked. Her self-described interests in the “appealing qualities of ugliness” are reflections of our own perversions; each exit in a Prada show is a rejection of an archaic paradigm.

A NEW PERSPECTIVE

In the Prada lexicon, aspirational means inspirational, and beauty synonyms with dignity. There’s no shape, no scar—either physical or emotional—neither age nor race that can prive you from your desired destiny, because you are the one who pens it.

For Miuccia, the search for beauty starts with our obsessions…with youth, with sexier bodies, faster cars or fleeting fame. Her designs, her world and her inventions teach us how to understand these obsessions, instead of just acting upon them, so the next time instead of in front of a mirror, we can get dressed with the idea of a better self.